The Commons vs Creative Commons I: From Ostrom to Postcapitalism - and Back Again

Saturday, June 14, 2025 at 6:23PM

Saturday, June 14, 2025 at 6:23PM This is an initial draft of a 5,000 word specially commissioned piece on the commons and Creative Commons. It’s for an open-access online glossary on the contemporary condition and near future that's being produced by the Chinese Academy of Art. Other contributors to the glossary include Felix Stalder, Jason Moore and Hannes Bajohr.

Contents:

I: Introduction * Conceptual Overview * Elinor Ostrom and the Tragedy of the Commons * Liberal Commons * Radical Left Commons * From Capitalism to Postcapitalism – and Back Again

II: The Undercommons * Latent Commons * Uncommons * The Unknown Common * Common Misunderstanding No.1: The Commons is Not Inherently Left-wing

III: Creative Commons * CC and AI * Common Misunderstanding No.2: Creative Commons is Not a Commons * The Commons and Creative Commons: Some Distinctions * Alternatives to Creative Commons

iV: Conclusion: Common Misunderstanding No.3: Commoner is Not an Identity * Common Misunderstanding No.4: There is Not One Commons

---

Introduction

The concept of “the commons” has one of its historical origins in the idea of shared lands – fields, meadows, pastures, woods – collectively owned, used and managed by a community. In traditional English law, such communal spaces were known as commons. Starting in the late medieval period, many were appropriated for private use and ownership through a process referred to as the “enclosure of the commons.”

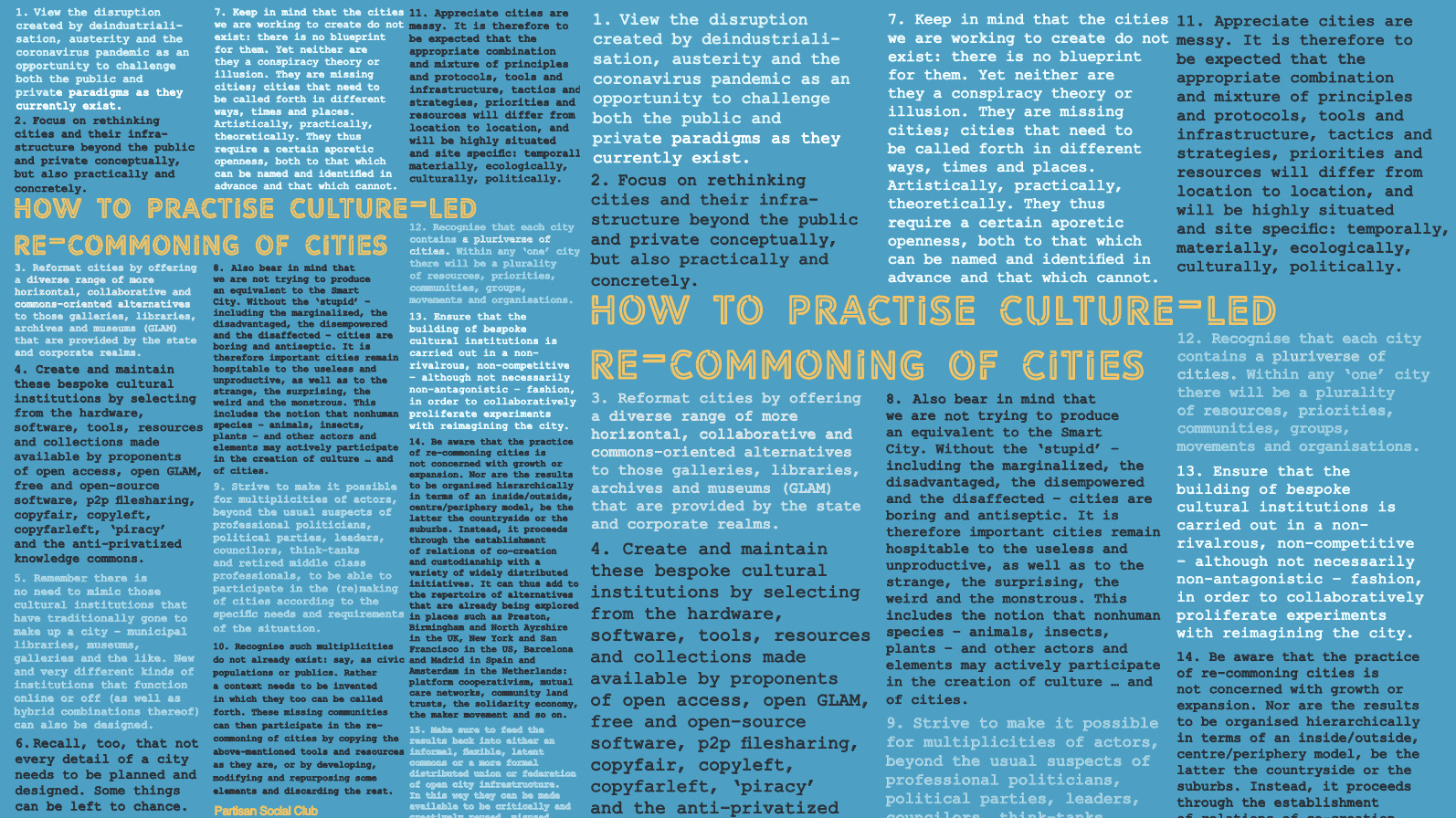

A common image of a commons

A common image of a commons

Over time, the term has expanded to take in a wide range of collectively held and accessible resources. Among them are:

- natural commons – animals, forests, fisheries, rivers, air, the earth;

- social commons – including some Indigenous knowledge systems and traditions;

- urban and political commons – such as those established during protests, assemblies, occupations of public spaces, squares and so forth;

- money commons – also known as tontines in various regions in Africa, a form of “autonomous, self-managed, women-made” banking system (Federici 2016);

- digital and networked commons – as associated with peer-to-peer (p2p) production, platform cooperativism and Free/Libre and Open-Source Software (F/LOSS) communities.

For centuries, the concept of the commons has been at the heart of debates over collective ownership and community governance.

Creative Commons (CC), by contrast, is a modern initiative. Founded in North America in 2001, it is a nonprofit organization dedicated to the free provision of alternative copyright licenses. These CC licenses enable creators to share and build upon works while remaining within the confines of the existing copyright laws. Though Creative Commons is often regarded as an example of the commons in the digital age, it is important to understand that there are fundamental differences between the commons and Creative Commons.

Conceptual Overview

Traditionally, “the commons” refers to land and resources that are controlled neither by private ownership nor the state; instead they are owned and shared by a community of commoners. Importantly, the idea of the commons can also encompass the social and economic processes and institutions through which commoners create, steward and maintain both the shared assets and their community. Access and use are here governed collectively and equitably by a specific group of users according to mutually agreed-upon rules. Each member of the community therefore has a stake in, and rights over, the commons.

Elinor Ostrom and the Tragedy of the Commons

The work of Elinor Ostrom, who received the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 2009 for her research on the commons, demonstrates that local communities can successfully co-manage and conserve shared ecological and environmental resources without the need of privatisation or centralised state intervention (Ostrom 2015). Ostrom’s studies counter the tragedy of the commons, a concept popularized (though not originally coined) by Garrett Hardin, along with the term “commons” itself, in his article of the same name (Hardin 1968). Hardin maintains that individuals acting in their own short-term self-interest will inevitably deplete common resources: through overgrazing or overfishing, for example. Despite frequently being used to justify the privatisation of the commons and removal of those who common, this argument assumes an absence of management or rules. In reality, commons are typically governed by social contracts and agreements that regulate use for both individual and collective benefit and prevent abuse, exploitation and neglect. Indeed, it is precisely this system of participatory self-governance that distinguishes commons from land and resources to which there is simply open and free access (a city street in which people are able to socialize and children play, for example). Any tragedy is the result not of the commons, then, but of people operating as individuals in their own interests to maximise their private property.

Liberal Commons

Philosophers, anthropologists, economists and political theorists have long debated the commons, particularly in relation to capitalism. Liberal perspectives today tend to view the commons as a supplement to capitalism rather than a direct alternative. They focus on preserving and expanding access to common pooled resources while protecting them from excessive commodification and control by either market or state. The influence of this liberal approach is evident in the use of Creative Commons licences by those open-access publishing organisations that look to build a global knowledge commons within existing economic structures through the sharing of the academic research literature – as opposed to fundamentally transforming those structures.

Radical Left Commons

More radical left interpretations see the commons as offering a practical political alternative to capitalism. Instead of being controlled by the market, including market socialism, or even the central state planning of the Keynesian left, resources and spaces are here created and governed collectively by a community of users who self-manage them in a horizontal and participatory – rather hierarchical, authoritarian, top-down – manner. Advocates contend that commoning – the social processes through which both the commons and the community of commoners are built and sustained – acts as a form of resistance to capitalist accumulation, extraction and exploitative wage labour, including reproductive and domestic labour. In this view, commoning is based on shared political principles and practices of co-ownership and co-belonging, such as freedom, equality and social justice. At the same time, commoning offers a foundation for actively crafting radically different non-capitalist ways of working and living together, politically, economically, culturally and environmentally: by revolutionising the home and neighbourhood through collective housekeeping, for instance, or separating the common wealth produced by communities from the military-prison industrial complex. For some, these alternative forms of sociality and cooperation even have the potential to be communist, in that they are often characterised by the elimination of private property, non-capitalist modes of production, consumption, distribution, valuation and exchange, and cultivation of new forms of (common) subjectivity.

From Capitalism to Postcapitalism – and Back Again

Others go further still. They position the commons not only as central to anti-capitalist and anti-colonialist movements seeking to disrupt dominant power structures, and as a strategy for reclaiming public resources following their historical and global enclosure (Bollier 2002; Harvey 2012; Linebaugh 2014). They also envision a commons reimaged for the 21st century as a political event, a starting point for transitioning out of capitalism to more just and equitable postcapitalist societies (De Angelis 2017).

These emergent political forms are rooted in diverse philosophies and imaginaries. They include:

- decentralized, cooperative, peer-to peer networks (Bauwens, Kostakis and Pazaitis 2019);

- economies of post-development and post-extractivism, degrowth and post-work (Gorz 1980; 1999);

- systems of solidarity, mutual aid and collective care: of the young, old and ill, and extending to care for the natural world (Federici 2018).

Debate persists, nevertheless. Do the commons – like communism for Marx – have to emerge out of capitalism and its contradictions? Antonio Negri argues that capitalism actually “creates the common:” that Marx doesn’t have a pre-capitalist conception of the common (Negri 2003). Here, the common and capitalism aren’t opposed, the one operating as a parallel alternative to the other. The common is impossible without capitalism. (As well as “the commons” Autonomist Marxists such as Negri often refer to “the common,” by which they mean those social relations that are a feature of post-Fordist capitalism’s dominant mode of production. In this context, the common is understood as a foundational condition for the emergence of the commons. As Negri puts it when writing with Michael Hardt: “one might say that the common is what we share or, rather, it is a social structure and a social technology for sharing” [Hardt and Negri 2017, 97].) The key question for Negri is how to separate the common – in the sense of abstract labour “that gets appropriated by capital and becomes common” – from exploitation (2003).

Yet must the commons (and common) always be defined in relation to capitalism: as that which arises out of capitalism, or refuses, resists, undoes or otherwise works through and transcends it, as the concept of postcapitalism implies (Dardot and Laval 2019)? And might a comparable question be raised regarding the state? That is, can the commons and its redistribution of public property and public good only take shape within, and simultaneously in opposition to, particular configurations of the state and state infrastructure (e.g. communications, education, health, sanitation, transport)?

Gary Hall | Comments Off |

Gary Hall | Comments Off |