On liquid, living books: Shakespeare and the Bible

Wednesday, December 14, 2011 at 11:50AM

Wednesday, December 14, 2011 at 11:50AM I began this series of posts by suggesting the word ‘book’ should not be applied to an open, decentered, distributed, multi-location, multi-medium, multiple-identity text generated out of a collaborative relationship with a number of different, often anonymous and unknown authors, as without being tied or fastened tightly together -- by the concept of an identifiable human author, for example -- such a text is not a book at all: it is ‘only’ a text or collection of texts.

•

To sample Sol Lewitt, we could say that one usually understands the texts of the present by applying the conventions of the past, thus misunderstanding the texts of the present. That, indeed, is one of the problems with a word such as ‘book’. When it is used -- even in the form of e-book, ‘unbound book’, ‘unbook’ or ‘the book to come’ -- it connotes a whole tradition and implies a consequent acceptance of that tradition, thus placing limitations on the writer who would be reluctant to create anything that goes beyond it.

•

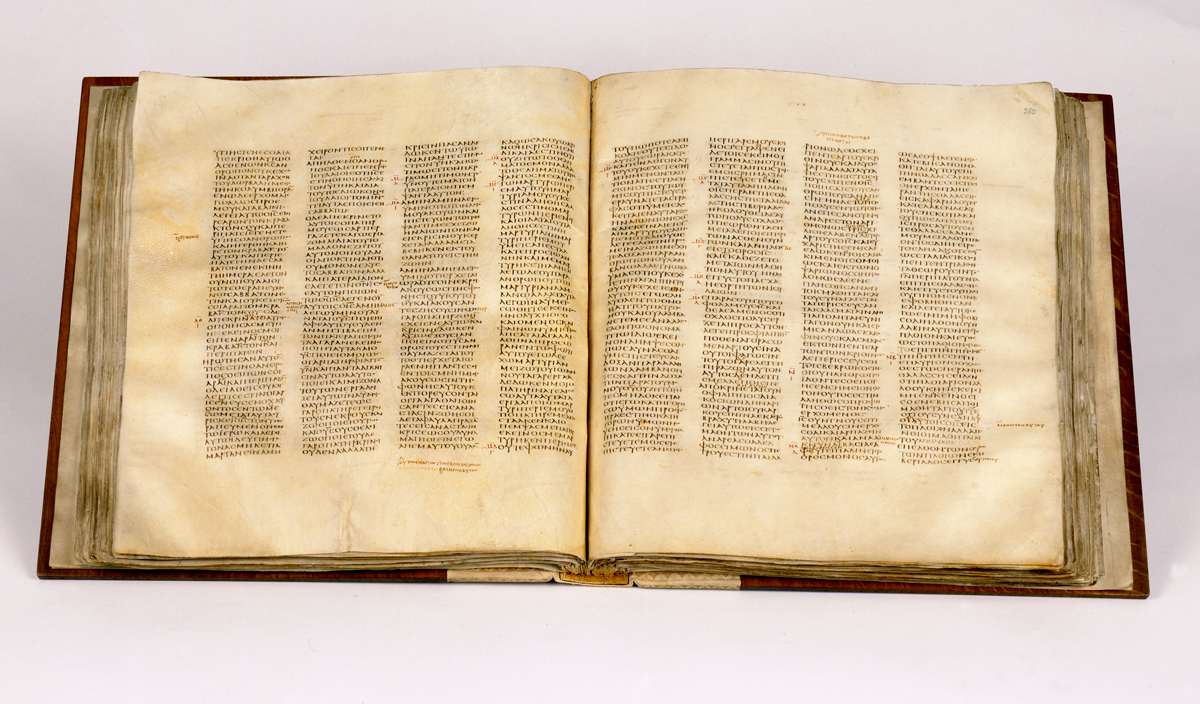

Then again ‘book’ is perhaps as good a name as any, since books, historically, have always been more or less loosely bound. Take the Codex Sinaiticus, the oldest surviving Bible in the world, and the ancestor of all the Christian Bibles we have today. As it currently exists, it is incomplete. Nevertheless, the Codex Sinaiticus still includes all of the New Testament, half of the Old Testament, and two early Christian texts not featured in modern Bibles, all gathered into a single unit for the very first time. So it is the first Bible as we understand it. But more than that, it is also one of the first large books, as to gather together so many texts which had previously existed only as scrolled documents required a fundamental transformation in binding technology that eventually saw the scroll give way to the codex book.

Just as interesting however is the fact that the Codex is also history’s most altered biblical manuscript, containing approximately 30 corrections per page, roughly 23,000 in all. And these are not just minor corrections. For instance, at the beginning of Mark’s Gospel, Jesus is not described as being the son of God. That was a revision added to the text later. In the original version, Jesus becomes divine only after he has been baptised by John the Baptist. Nor is Jesus resurrected in the Codex Sinaiticus. Mark’s Gospel ends with the discovery of the empty tomb. The resurrection only takes place in competing versions of the story that are to be found in other manuscripts. Nor does the Codex contain the stoning of the adulterous woman – ‘Let he who is without sin cast the first stone’; or Jesus’s words on the cross – ‘Father forgive them for they know not what they do’.

So the Bible -- often dubbed ‘the Book of Books’ -- cannot be read as that most fixed, standard, permanent and reliable of texts, the unaltered word of God. On the contrary, the text of the Bible was already seen as being collaborative, multi-authored, fluid, evolving, emergent when the Codex was created in 350 AD.

•

Another example is provided by Shakespeare’s First Folio. As Adrian Johns has shown, this volume includes more than six hundred typefaces, along with numerous discrepancies regarding its spelling, punctuation, divisions and page configurations. Indeed, the Royal Shakespeare Company recently opened its newly renovated theatres in Stratford with productions of Macbeth and Cardenio, a previously unperformed work by Shakespeare. Yet Cardenio, a missing 1612 tragedy by Shakespeare and Fletcher, may contain hardly anything by Shakespeare at all, while Thomas Middleton is now thought to have been heavily involved in the writing of Macbeth. In fact, Macbeth, Timon of Athens and Measure for Measure are all also to be found in Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino’s collected works of Thomas Middleton.

•

We could thus say that books have always been liquid and living to some extent: digital technology and the internet has simply helped to make us more aware of the fact.

(This is one of a series of posts written as version 3.0 of a contribution to Mark Amerika's remixthebook project. For other posts in the series, see below and here)

Reader Comments